By Doug Beinborn

Vizient Associate Principal

While the median age at diagnosis for atrial fibrillation (AFib), an irregular and rapid heart rhythm, is 75, it can affect a wide age range of the population with the incidence increasing rapidly. It is estimated by Circulation Research that 6 million citizens are currently affected by AFib and is expected to grow to 16 million by 2050. This is partly due to the aging population, but also can be attributed to increasing sedentary lifestyles, the obesity epidemic, sleep apnea and skyrocketing incidence of diabetes.

Upon diagnosis, patients are typically treated with a combination of medication and recommended lifestyle modifications. New data, however, point to an opportunity to challenge current care strategies for these patients.

A recent study, published in May 2023 by the American Heart Association (AHA) and conducted at Cleveland Clinic, found that ablation — a procedure done to restore a normal heart rhythm — was an effective strategy in young adults with AFib. The study included 241 younger adults (16-50 years old) in the cohort. It reported that 77% of the patients were free of atrial fibrillation at one year after treatment while 90% reported improvement of atrial fibrillation after five years. These results underscore an important consideration: while ablation is traditionally reserved for older patients with advanced progression of the disease, other factors such as quality of life and medication adherence and/or side effects could justify the procedure earlier for a broader population base.

Treatment goals and options for patients

The primary goal of treatment is to reset the heart into a normal sinus rhythm. The second is to control the heart rate while remaining in AFib to avoid symptomatic bradycardia (a slower than normal heart rate) or tachycardia (a heart rate over 100 beats per minute). Avoiding blood clots through anticoagulant medications also is a consideration to mitigate stroke or other embolic conditions that may accompany AFib. Because of the risks associated with AFib, and the effects it can have on an individual, it is important for healthcare professionals to work closely with the patient to maintain the patient’s quality of life as well as manage and mitigate related health implications associated with the disease.

Focusing on the primary goal, resetting the heart rhythm, is achieved by two cardioversion methods, electrical cardioversions or antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs).

Electrical cardioversions are typically performed in a hospital and require short-acting anesthetics. This method requires an electrical shock delivered to the heart through paddles or patches placed on the chest.

AADs, including medications such as propafenone and amiodarone, are typically administered for two or more days to achieve results.

If cardioversions fail to keep the heart in normal sinus rhythm, a patient may be referred to an electrophysiologist to discuss more invasive curative options. These options include surgical ablation or catheter ablation.

Surgical ablation uses radiofrequency or cryotherapy and requires an invasive approach since this is performed on the external part of the heart and necessitates both a cardiac surgeon and electrophysiologist.

Catheter ablation, however, can be performed by various energy sources. Cryoablation uses freezing technology to create lesions while radiofrequency creates thermal energy to disrupt tissues. Pulsed field ablation creates strong electrical fields that is cardiovascular tissue specific to create desired effect.

Each of these methods can be effective but early data suggests PFA could have the lowest risk of injury to the phrenic nerve, esophagus and blood vessels. PFA creates lesions through non-thermal methods through irreversible electroporation, or high-voltage pulses used to create microscopic pores in cell membranes.

According to Sg2, a Vizient company, all major intracardiac catheter ablations will have a cumulative five-year growth rate of 24%. Diving into the numbers, they are higher for older adults, 31% for ages 65 and older. However, there is still a projected increase of 14% in the 45-65 age group and 16% in the 18-44 age range. Looking at a 10-year projection, those under 65 are anticipating a 27% increase in ablation procedures.

A progressive disease state, requiring progressive care

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia observed in clinical practice, currently affecting 5.6 million Americans and expected to grow to 12.1 million cases by 2030. Despite the treatment options currently available for AFib, the condition is almost always progressive, requiring lifelong therapy.

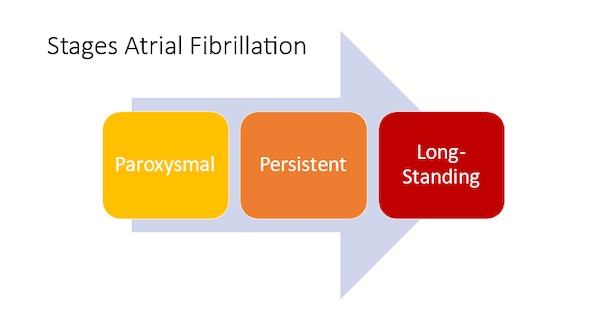

While early on in the disease AFib episodes may be spaced out over longer periods of time, the episodes often become increasingly frequent and more intense — necessitating more aggressive therapy. The progressive stages of AFib are paroxysmal (episodes terminate spontaneously), persistent (episodes continue for more than several days and require medication or cardioversion to terminate) and long-standing (drug and cardioversion treatments are unsuccessful).

Knowing that younger patients are likely to advance through these stages, it could be argued that earlier ablation intervention reduces the total cost of care and improves quality of life by eliminating the need for medication adherence and potential drug side effects — not to mention reducing the risk of stroke, heart failure and other AFib-related complications.

Growing prevalence plus younger incidence

Previously, most clinicians felt that AADs should be implemented as the first-line therapy for AFib, reserving ablation as an option only after one to two drug failures. That thought process is evolving as new data becomes available, such as the aforementioned Cleveland Clinic Study.

Additional clinical studies support this potential shift in the management of arrhythmia care. The EAST-AFNET 4 trial showed that early rhythm control resulted in superior cardiovascular outcomes compared to usual care at five years of follow-up.

Use of first-line AADs showed undesirable side effects including organ toxicity, pro-arrhythmia, depression and feeling sluggish. Initial randomized trials comparing AAD’s to AFib ablation for initial first-line therapy showed significantly lower incidence of additional arrhythmias. Analysis points to a reduction of 38% in atrial arrhythmias and a 68% reduction in hospitalizations compared to AAD’s.

A call to action: considering ablation as a first-line therapy

As wearable devices become increasingly accessible — and accurate — we anticipate that earlier detection of this disease will be even more prevalent. Patient self-collected data may prompt patient self-referrals, often at a younger age. This highlights a potential for greater demand for care and a need to be prepared to treat younger patients.

Utilizing ablation as first-line therapy, as opposed to AADs, should be considered to improve outcomes while reducing costs. It is important for providers to work with patients to assess each individual’s best therapy. However, looking at ablation therapy, combined with risk modifications, could help providers obtain the best long-term outcomes for many younger adults diagnosed with AFib.

Additional Resources:

- Dysrhythmia and new tech impacting your electrophysiology program

- Top 10 questions about pulsed field ablation

About the author

Doug Beinborn is the Associate Principal at Vizient and works directly with cardiovascular suppliers and members. His experience cardiology spans over 30 years within clinical practice, research operations and new product development. Beinborn received his Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Viterbo University and his Master of Healthcare Administration from St Mary’s University of Minnesota. He is an active member of Heart Rhythm Society and has served on various roles including the HRS Board of Trustees.